Quatermass

Nigel Kneale's Quatermass has often

been called "the Grandfather of British Television Sci-Fi" - and not without

reason. For although it was not the first home-produced TV SF - adaptations of both 'The

Time Machine' and 'R.U.R.' predate it, for example - there is no doubt that it was the three Quatermass

serials that etched their mark most deeply into the public psyche. Over half a century

later, all three stories are finally getting the release which has long been awaited...

The three Quatermass serials - The

Quatermass Experiment (1953), Quatermass II (1955) and Quatermass

and the Pit (1958) - were produced by the legendary Rudolph Cartier, in

an era in which live television transmission was the norm and any kind of

television recording system was still in its infancy. In fact, the last serial

was transmitted only scant months after the first Ampex Quadruplex video tape

recorder was delivered to the BBC (in July 1958) and the second machine was not

delivered until early 1959. It would be a few more years before the BBC were

routinely using videotape for drama programmes. All three serials were transmitted live from BBC studios in

London, using the 405-line television system - literally a live, multi-camera studio

performance with pre-filmed 35mm inserts played in from telecine. These inserts served the

dual role of allowing the story to spread to locations beyond the confines of the

television studio, and of allowing time for the actors and cameras to move to the next

studio set.

The three Quatermass serials - The

Quatermass Experiment (1953), Quatermass II (1955) and Quatermass

and the Pit (1958) - were produced by the legendary Rudolph Cartier, in

an era in which live television transmission was the norm and any kind of

television recording system was still in its infancy. In fact, the last serial

was transmitted only scant months after the first Ampex Quadruplex video tape

recorder was delivered to the BBC (in July 1958) and the second machine was not

delivered until early 1959. It would be a few more years before the BBC were

routinely using videotape for drama programmes. All three serials were transmitted live from BBC studios in

London, using the 405-line television system - literally a live, multi-camera studio

performance with pre-filmed 35mm inserts played in from telecine. These inserts served the

dual role of allowing the story to spread to locations beyond the confines of the

television studio, and of allowing time for the actors and cameras to move to the next

studio set.

The recordings that survive - the first two episodes

of The Quatermass Experiment and all six episodes each of Quatermass

II and Quatermass and the Pit - are preserved as 35mm film

recordings. Film recording was still very much in its infancy in 1953 - and indeed there

is much evidence to suggest that the final four episodes of the first serial were never

even recorded, because it was felt that the recordings of the first two episodes had been

so poor that it was not worth continuing with. Only two years later however, technology

had moved on enough to allow passably good recordings of Quatermass II to

be made, and by the time Quatermass and the Pit transmitted, the

recordings were of very high quality indeed.

In approaching the restoration of these serials for

DVD release, we were mindful of the variable quality of the recordings and of the limits

placed upon us by both time and budget, so it was decided to spend significantly more of

both of the latter on the story which we felt would benefit the most - Quatermass

and the Pit. So the story of the restoration of these serials begins with the

newest and works backwards from there...

Quatermass and the Pit was performed from

Riverside Studios in Hammersmith and recorded using a 35mm stored-field film recording

system. This was a system designed to get round the mechanical impossibility of advancing

the film forward a frame within the 'field blanking interval' - the very short dead time

between the two interlaced TV fields that make up one frame. Only a few years earlier, Quatermass

II had been recorded using a suppressed-field recorder, which only exposed one of

the two video fields to film, using the duration of the second field to close the shutter

and move the film on in readiness to expose the next frame. This meant that the vertical

resolution of the suppressed-field image was less than two hundred lines, resulting in a

very coarse, steppy image. Stored-field got around this problem by 'storing' one field

using the long decay time of the phosphor coating on the film recorder's cathode ray tube

and allowing an entire 20mS field period to allow the film to be advanced to the next

frame. During the first field, the camera shutter would be closed and the film would be be

advanced. At the same time, the first field would be written out to the CRT at a very high

intensity, so that the image retained by the phosphor afterglow would still be visible

20mS later when the shutter was opened and the second field was written 'live', interlaced

between the lines of the fading image of the first field. The live field was written at a much

lower intensity, so that its level matched that of the stored field, resulting in a full

resolution picture being captured onto the film.

Quatermass and the Pit was performed from

Riverside Studios in Hammersmith and recorded using a 35mm stored-field film recording

system. This was a system designed to get round the mechanical impossibility of advancing

the film forward a frame within the 'field blanking interval' - the very short dead time

between the two interlaced TV fields that make up one frame. Only a few years earlier, Quatermass

II had been recorded using a suppressed-field recorder, which only exposed one of

the two video fields to film, using the duration of the second field to close the shutter

and move the film on in readiness to expose the next frame. This meant that the vertical

resolution of the suppressed-field image was less than two hundred lines, resulting in a

very coarse, steppy image. Stored-field got around this problem by 'storing' one field

using the long decay time of the phosphor coating on the film recorder's cathode ray tube

and allowing an entire 20mS field period to allow the film to be advanced to the next

frame. During the first field, the camera shutter would be closed and the film would be be

advanced. At the same time, the first field would be written out to the CRT at a very high

intensity, so that the image retained by the phosphor afterglow would still be visible

20mS later when the shutter was opened and the second field was written 'live', interlaced

between the lines of the fading image of the first field. The live field was written at a much

lower intensity, so that its level matched that of the stored field, resulting in a full

resolution picture being captured onto the film.

Two film recorders would have been used to record

the shows as they were transmitted, each one recording approximately nine minutes of

material before the other was run up to record the next section. The operators would try

to ensure that there was an overlap of one entire shot recorded by both machines, so that

the reels could subsequently be joined at a shot-change, rather than mid-shot (which would

have highlighted geometrical and other differences between the two recordings).

All six episodes of the serial exist as 35mm film

recordings with combined-optical soundtracks. There is also a two-part compilation version

of the story, which was broadcast in the early sixties, which has some material trimmed

out to fit into the required running time. Before any real transfers got underway, we

carried out tests to ascertain if there was any advantage in transferring the original

film recording negatives rather than prints made from them, and also if we could utilise a

less-expensive telecine than the Spirit we tend to use for 16mm transfers. This showed

that, because the 35mm frame is large and the 405-line image has limited resolution, there

was no perceivable quality difference between using the prints or the much more valuable

negatives, or between the Spirit and the less expensive Cintel Ursa Diamond flying-spot

telecine.

The Ursa also gave another advantage, in that it has

the ability to alter the shape of its scanning spot. In this case, we could elongate it so

that it effectively slightly defocused the image vertically, helping to break up the

visible line-structure of the 405-line raster. A later development of the film-recording

process would be a technique called 'spot wobble' which would do very much the same thing,

but in the film-recorder itself.

To begin the restoration process, the prints were

called up, ultrasonically cleaned, and transferred 'one-light' on the Ursa to Digital

Betacam videotape by the RT's Jonathan Wood. Each episode was then digitally graded and

DVNRed tape-to-tape, cutting out a couple of dirty frames at each vision cut so that shot

changes were nice and clean.

From an earlier experience of running the

compilation version, Steve Roberts was aware that when

the BBC re-edited the serial into the compilation

format, they had actually gone back and cut-in the original 35mm insert films in place of

the film-recorded versions of the same. So true 35mm film quality material was available

for large chunks of the show! Therefore it had always been our intention to telecine these

parts of the compilation as well, digitally editing them back into the individual episodes

where possible. However, it quickly became apparent that we were going to have to transfer

all of the material in the compilation reels, not just the film sequences...

The reason for this was tied-in with our desire to

achieve the best possible quality in both pictures and sound. When the serial was

originally recorded, the programme sound would have been recorded in two ways - as the

combined-optical track on the picture film, and as a separate 35mm magnetic soundtrack of

much higher quality. Sadly, the sep-mag soundtrack films were junked at some point in the

past, so only the com-opt tracks on the episodes still exist. However, because the

original mute film sequences had been physically cut back into the compilation version,

the compilation never had a full com-opt soundtrack - it had a sep-mag soundtrack that had

been edited down from the original episode sep-mags before they were destroyed. The

compilation sep-mags still exist (albeit as 16mm polyester safety dubs from the decaying

35mm acetate mags) and the sound quality was massively better than that available from the

com-opt tracks on the episodes. Therefore not only were the compilations going to be

needed to provide a large picture-quality increase for much of the programme length, they

would also be providing better quality sound for most of the time as well! The

lower-quality com-opt soundtracks would only be needed to bridge the sections which had

been cut out of the compilation version - which was great from a quality viewpoint, but an

unexpected headache for Mark Ayres, who would now also be responsible for patching

together the best sound from two entirely different sources as part of his audio

restoration work... Here, Mark

describes the work he did to bring the audio side of the story up to scratch:-

After the episodic pictures were to

length, with any rough vision edits repaired and film sequences replaced, they

were dubbed to DVCam tapes and sent to me. These tapes

still contained the optical sound from the original telerecordings. I also

received DVCams of the two-part

compilation version, with the 16mm magnetic sound. All of these materials were

captured into Final Cut Pro on the Macintosh, maintaining the programme timecode

on the episodes for reference, then dropped into Nuendo and the soundtracks

imported onto tracks for treatment.

With the episodes on the timeline, I

then went through all six programmes match-cutting the magnetic sound to sync.

Where scenes had been cut from the compilation, I dragged the relevant optical

sound onto a "keeper" track for use, retaining the full synchronised master

track for later reference. I ended up with a patchwork of audio clips, all

synchronised with the pictures but needing restoration. The 16mm mag tracks are

copies of the original (lost) 35mm mag. I suspect that they are in effect a

salvage dub as they are a little rough in places - perhaps the 35mm had started

to decay. Nevertheless, they are far better than the optical sound, with less

noise, distortion and sibilance.

One thing I immediately noticed is that

the levels on both the optical and mag tracks are very variable - one suspects

that they did not have particularly sophisticated gain control devices in the

studio at the time and relied on the transmission limiters to cope...however

they also often kept the level very low, perhaps expecting a loud peak which

never came. This was a side effect of making the original programmes "live", but

it can be corrected in mastering with some careful riding of the dynamics and

leads to a far more even and acceptable listening experience to modern ears. (I

later discovered that neither "The Quatermass Experiment" nor "Quatermass II"

suffer from the same problem to anything like the same extent, which makes the

varying levels on "The Pit" even more baffling.) More worrying was the

occasional off-mic or very quiet line which tended to disappear beneath the

noise floor. Hence I had to carefully ride the noise reduction levels at times

to avoid filtering required sound with the hiss!

Despite the credit for "music specially

composed", the score for this story was all from "stock": library tracks

composed by the great Trevor Duncan. A prolific composer, Duncan's output was so

great that no single library was ever able to publish it all, so his work

appears across numerous labels: Boosey & Hawkes, KPM, Conroy, Impress...to name

but four. After much digging through the archives and many emails and telephone

calls, I was able to secure new copies of a number of tracks including

"Mutations" from the KPM library (used for the opening titles, all closings

except episode six, and in other places as well), "The Conquest of Space: Escape

Velocity" (used for the recaps in episodes two, three

and four) and "Cathedral: Vision", which

closes episode six. It makes a big difference to open the show with a really high

quality copy of "Mutations", and the new copy of "Escape Velocity" helped

enormously in cleaning up the recaps - all of which, barring episode

four's (which opened the second compilation episode) only exist on the

optical track. Nevertheless, it is these recaps which remain the least

satisfactory part of the restoration, the original mix being less than perfect.

"Mutations" was originally released on the Conroy mood music label, and KPM -

who now own the rights to that library - were kind enough to send me a new

digital copy direct from the master tape. Ironically, we also found a copy of

the original 78rpm disk in a storeroom at BBC Pebble Mill. I had hoped to

replace some additional music cues: the recaps at the start of episodes

five and six

and that accompanying the appearance of Hob over the dig. But this music, Trevor

Duncan's "Four Evil Men" suite, eluded us. The BBC no longer hold copies of

those 78rpm library disks (the few at Pebble Mill being retained simply because

nobody had ever cleared out this particular storeroom) and even the original

library, Boosey & Hawkes, no longer have it. For my future pleasure, I am

continuing the search, and resign myself to the fact that copies will

undoubtedly surface a few days after I deliver the final masters!

Clicks and pops were removed where

appropriate, but I went easy on correcting "mistakes" unless they were very

distracting - this was, obviously, live television, and I do not think that we

should disguise that fact. I was very tempted on a couple of occasions to add in

additional or alternative effects (for instance, the very wooden thud of

pickaxes in the pit, or the hollow thump and boom of feet on the wooden rostra

that formed the floor of the supposedly metal inner surface of the capsule), but

resisted. For the same reason, editorially, the RT has left in a couple of

instances of actors obviously waiting for cues, which were actually cut out on

the original repeat compilation version. To us, it all adds to the excitement of

this being "live". Though I did tone down the frequent off-camera coughing fits

of one crew member in episode three...and I removed a prominent microphone knock in

episode four.

During the opening film shots of the

crane in episode one, there is some flanging / double-tracking on the sound -

this is present on both the mag and the optical, so is probably an error on the

original recording, or could even be due to a poorly-positioned microphone on

location. There is also a fair amount of distortion on this sequence (the noise

of the scoop, the foreman shouting) which is deeply ingrained and impossible to

shift.

Matching the 35mm optical sequences to

the mag track was tricky at times, as it was far noisier. In many instances I

resorted to using very heavy noise reduction, then rebuilding the background

behind the track - for instance in the episode one scene with the reporter doing "vox

pops" outside the dig. This was not possible, of course, where there is no

background sound to rebuild - office scenes in the later episodes, for instance.

In these cases, I have tried to disguise the joins in various ways, or at least

make them less objectionable. But there is an unavoidable rise in the noise

floor, and constraint of the frequency range, at these transitions and, in order

to make them more even, I backed off on the noise reduction of the magnetic

tracks on these sections as well. There is always a trade-off...a couple of

optical sound sequences in episode three proved particularly difficult to match in

to the mag - mainly because the transition from one to the other was too much of

a jolt mid-scene. In these cases, the optical sound has been "held" longer than

one would like, in order that the transition may be better disguised.

Episodes two and

six were particularly

affected by little electrical clicks which have now been removed, while

episodes three and

six had many dropouts which were not present on the optical track, and which

must therefore have been copied from the decaying 35mm original, or are a

dubbing fault. All were patched, occasionally from the optical track.

During the scene in which Quatermass is

summoned back to the War Office in episode four, there is a lengthy dropout on the mag track, where the level dives by about 8dB and then creeps back up again.

Counteracting this necessitated programming level changes, noise reduction

threshold and a low pass filter dynamically. The effect is not inaudible, but

proved less distracting than temporarily switching to the optical track. Similar

gain riding was necessary in episode six, much of which was originally recorded

at an extraordinary low level - the big riot scene was about 8dB below peak, for

example, which rather lessened its impact. (To give you some idea, a drop of 6dB

can be perceived as a halving in volume - so I have in effect more than doubled

the volume of this sequence!)

One nagging problem remained at the end

of all this - one large unrepaired fault which really bugged me. In episode

one,

at about 08:10, Roney is showing off his model ape. He says, "Now these modelled

portions that you see are what we've found so far....he wasn't very tall".

Annoyingly, the words "modelled portions" and "tall" are obscured by distortion.

The problem is present on the mag and the optical, so probably happened in

studio or on studio output - possibly a dirty connection somewhere. And the

noise doesn't just obscure these words, it totally replaces it - so no amount of

de-clicking, de-crackling or drawing was going to fix it. It is obvious from the

context (and Nigel Kneale's script book!) what these words are but the bursts of

noise are distracting and spoil the scene.

Normally, when faced with this kind of

problem, I search elsewhere in a production for the same character saying the

same words - or at least the same syllables - and try to rebuild the affected

line. But I could not find any of these syllables ("mo-", "-delled", "por-", "-tions"

and "-all") anywhere in useable form. A couple of uses of the word "all" were

obscured by background noise or the inflexion was wrong. The word "important"

contains the "por-" but, again, the inflexion did not work. And, in any event,

"mo-", "-delled" and "-tions" eluded me entirely. So I was going to leave it.

But then, when running out the final masters, I heard it again and decided to

have another go...

So I have - sort of - solved the

problem of "tall" by cutting it a bit short and adding some reverb, which I

think is less distracting than the noise. But "modelled portions" was still

impossible to fix. In the end, I have done something a tad radical. I found some

other words, and pretty much seamlessly re-wrote the line so that it reads, "Now

these rough fragments that you see are what we've found so far...". Roney moves

behind someone at this point so the lipsync is obscured, and I think the line

still makes sense. The casual viewer will, I hope, not notice anything amiss,

whereas he *would* notice the burst of distortion. And I trust, therefore, that

both the purist fans and Mr Kneale himself will forgive me this little licence.

In common with the rest of the team, I

was probably more excited at the prospect of working on "Quatermass and the Pit"

than many other things we've restored recently. This despite the amount of work

it would undeniably take - and our budget and time was tight, with episodes up

to a third longer than "Doctor Who". But "The Pit" is a classic of the first

order: gripping drama that still holds up well. What I love about it is the way

the drama unfolds naturally, without being forced and without gimmickry. The

early episodes are leisurely - slow, even - by today's standards - but rather

than seeming "old-fashioned", it simply demonstrates to me all that has been

lost with the current fad for fast cutting, sensation, and the schedulers'

paranoia that the audience will lose interest and switch channels. That early

restraint also serves to underline the apocalyptic and genuinely shocking events

of the last episode - even if they take place almost entirely off-camera.

Quatermass and the Pit is a class act, whichever way you look at it.

The serial is also a lovely lesson in

technique, even if some decisions *do* seem strange by the standards of today.

For instance, they seemed to feel that music and effects could not co-exist.

Look at the sequence in episode one where Miss Dobson has her funny turn, or the

later sequence at about twenty-six minutes in, where the "bomb" is being

examined with a stethoscope: as soon as the music comes in, all the traffic

noise (which would have been played in from 78 rpm disk) disappears. This is

exposed even more now that I have removed the tape hiss and mains hum that

plagues the original recording. Of course, it may have been as much a technical

decision as an artistic one - with limited play-in decks available, the grams

operator may well have used the presence of the music as an excuse to re-cue the

traffic disk to make it last longer!

Quatermass and the Pit had

previously been released as a two-part compilation version by BBC Video on VHS in the

mid-eighties and latterly the same master had been used in Revelation's DVD release.

Strangely, BBC Video had elected to make up their own compilation version from the

episodic version, rather than by simply transferring the existing BBC TV compilation -

which meant that the original 35mm film sequences had never been a part of the commercial

release.

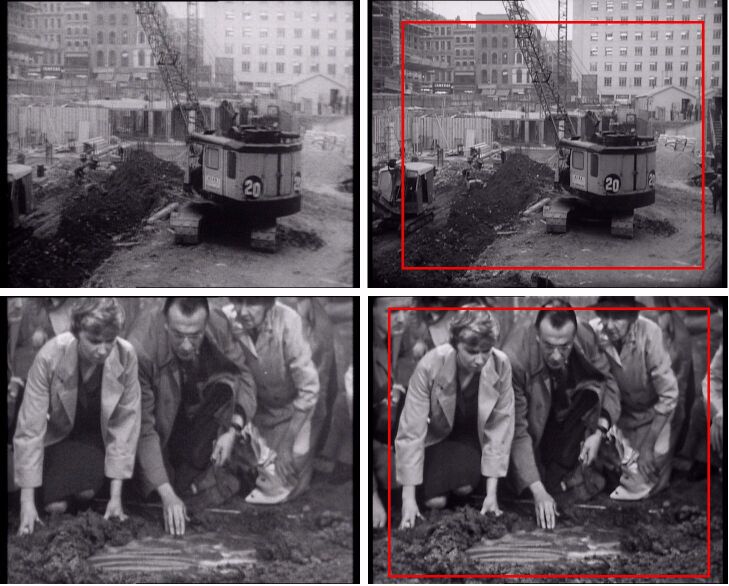

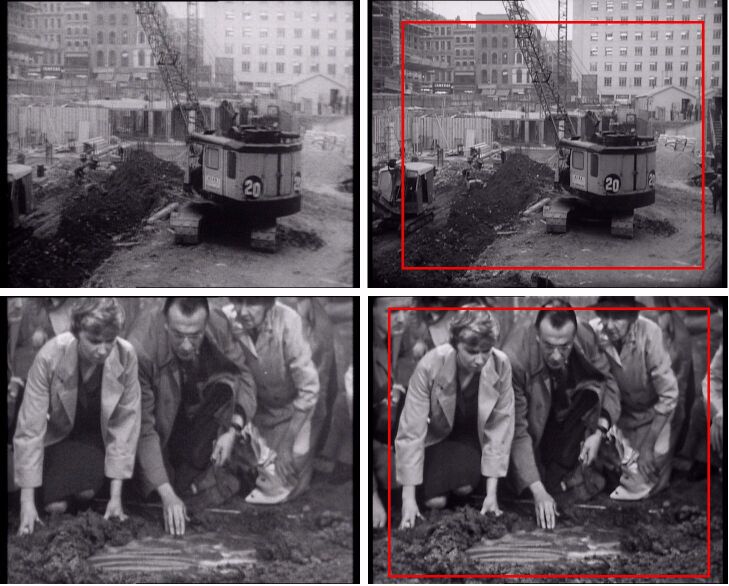

The following examples compare the original BBC

Video transfer (taken from Revelation's DVD) on the left against our new transfer on the

right. The area outside the red box superimposed on the new transfer is roughly the amount

that was missing from the earlier release simply because the entirety of the available

image had not been scanned before!

The top images are from the film sequences at the

beginning of the first episode and demonstrate how much additional image was lost due to

the scanning of the original film sequences in the 1958 telecine, compared to the lower

images, which are from the studio sequences. For a full-resolution look at the difference

between the film-recorded film sequence and the new transfer of the film sequence itself,

click on then roll your mouse over the following image:-

Surprisingly, considering its age, there were no

major nasty surprises awaiting us. The first two shots of the opening episode (a shot

panning down from the Hobbs Lane / Hob's Lane signs to the construction site,

followed by a shot of the contractor's sign) suffered from severe flicker, which we

assumed was a film recorder fault. However, the second of these shots exists as real 35mm

location film in the compilation - and was just as flickery! We can only assume that

there was a shutter fault in the 35mm camera, but they had no option but to use the shots.

These were de-flickered for us by Ian Simpson at BBC 3dfx using Furnace running on a G5

Mac.

In episode two, there is some bad luminance flashing

across the middle of the picture on a shot of Quatermass moving into the derelict house.

However, the break-up is over only a few frames in which actor Andre Morell is effectively

just sliding sideways over the background. This

was fixed using Furnace running on a G5 Mac to

generate 16 new clean frames between the last and first good frames surrounding

the fault. The background had very little detail and contrast so tended to morph

over a second which looked very false, so the background was painted back in as

much as possible. Finally grain from the surrounding film was sampled within

Combustion and then added to the replaced segment. Several shorter off-locks

were fixed with more conventional retouching.

Because many of the insert film shots mix to or from

the studio shots at their beginning or end, the compilation editor in the early sixties

had tried to maximise the amount of true film material by cutting from film back to the

film-recording just prior to the mix. This gave a nasty jump-cut, because the image on the

film recording was generally of a different size and quality to that on the film. In order

to avoid this, we used a number of techniques - let's assume we're coming to a transition

where the film mixes back to studio. The most obvious technique is to cut back to the film

recorded material right at the beginning of the shot which ends in the mix, which is very

easy to do, but reduces the entire shot back to film-recorded quality. Alternatively, we

could sacrifice some material from the end of the film shot and from the beginning of the

studio shot, remaking the mix electronically. We did this on a couple of occasions, but

only where it sacrificed nothing of importance - certainly we would not countenance loss

of any dialogue or important action. The other technique which could sometime be applied

was to match the geometry of the new transfer to that of the film-recorded version of the

transfer, mixing across between the two at a suitable point near the end of the shot. A

good example of this technique can be seen near the end of episode one, where

Roney runs

up the ramp out of the excavation. At this point, the film recording suffers from being

out-of-phase with the film, resulting in the classic double-imaging problem which is often

seen on film-recorded film inserts. To avoid having to take the entire shot double-imaged,

the beginning of the shot is from film and as the camera pans and blurs to follow

Roney up

the ramp, we mix back to the film recording over a second or so.

In episode five, there is a strange jump cut on the

scene where Roney runs over to steady Miss Judd, who is being influenced by the emanations

from the ship. Roney is at one side of the studio and then suddenly on the next shot he is

on the other side of the studio, steadying Miss Judd. As this is on a part of the live

studio action, it must have been cut out after transmission. Our first thought was that

the shot was on the boundary between two film recorder reels and that part of the shot had

not been recorded in the changeover, but when we checked the original film recorder

negatives, that shot was mid-reel. This lead us to assume that there was a technical fault on

the recording, most likely a large film recorder off-lock at this point, which had

subsequently been excised from the negative. However,

research by Andrew Pixley indicates that 1' 25" of the episode was re-performed

at the end of the recording, presumably to cover either a technical or artistic

problem encountered during the performance.

Episode five ends abruptly,

losing the caption announcing next week's episode. This

has been

re-created digitally in a matching style. The reason the material is missing is most

likely to be that it was right at the end of the film recorder's roll and the operator had

gambled that there would be enough film.

Following manual

clean-up of the pictures, a new and improved version of the VidFIRE videoising

process was used to return the fluid motion, video-look to all of the sequences

which were shot using electronic studio cameras. This is the only story of the

three where we judged the quality of the film recording process to be high

enough to enable VidFIRE to be applied convincingly.

The majority of Quatermass II was recorded from Lime

Grove studios in Shepherd's Bush using a 35mm suppressed-field film recorder and as such

it has much poorer image quality than Quatermass and the Pit. The

television line structure on these episodes is very visible and the picture itself is made

up of less than two hundred lines. For some reason episode three was recorded on a

different kind of recorder to the other episodes - it was probably a pair of Moye-Mechau

recorders (an upgraded version of the machine used two years earlier to record The

Quatermass Experiment, which used a Mechau mirror mechanism and a Moye camera).

The optical soundtracks produced by both these recorders was of the higher-quality

variable-area type - a significant improvment on the variable-density recording used on

Alexandra Palace's Mechau machines.

The majority of Quatermass II was recorded from Lime

Grove studios in Shepherd's Bush using a 35mm suppressed-field film recorder and as such

it has much poorer image quality than Quatermass and the Pit. The

television line structure on these episodes is very visible and the picture itself is made

up of less than two hundred lines. For some reason episode three was recorded on a

different kind of recorder to the other episodes - it was probably a pair of Moye-Mechau

recorders (an upgraded version of the machine used two years earlier to record The

Quatermass Experiment, which used a Mechau mirror mechanism and a Moye camera).

The optical soundtracks produced by both these recorders was of the higher-quality

variable-area type - a significant improvment on the variable-density recording used on

Alexandra Palace's Mechau machines.

All that now exists are the 35mm com-opt film

recorder negatives and prints, plus a few 35mm model sequences from

episode six. If magnetic

soundtracks ever existed, they are long gone now - and unfortunately the com-opt

soundtracks are very poor in places. What is particularly noticeable is how much poorer

the overall technical quality of the production is compared to Quatermass and the

Pit, which was only three years later. The studio cameras suffer from peculiar

black and white shading towards the edges of frame, so it is impossible to get a

consistent luminance level across the entire picture. The vision-mixer cuts appear to be

via a simple mechanical switch operating directly across the outputs of the cameras, and

the bounce in the switch contacts causes between two and seven frames of flashing and

distorted video at each cut. All of these distracting frames had to be edited out to make

the pictures more acceptable, offsetting the audio edit in order not to lose or damage any

dialogue in the process. The episodes are also plagued with variations in black level

throughout, often varying within a shot. Whether this was caused by automatic variations

in the recording chain (maybe some kind of automatic level control) or by engineers in the

studio changing the camera racks throughout the show, the net result is that a lot of time

had to be spent programming in dynamic grading changes in order to smooth out the

variations as much as possible.

As with Quatermass and the Pit,

tests showed that nothing was to be gained by using the negatives instead of the existing

prints, so generally the prints were telecined. The exception to this was the first reel

of episode five, which was found to be badly scratched, so the negative was used instead. In

part one, there is some damage to the picture and soundtrack caused by sprocket picking,

but it was found to be printed into the picture, indicating that the damage is to the

negative. There is also some fine vertical scratching during the opening few minutes

of episode one, which can also be seen on the clips of that episode used in

episode two,

suggesting that the film damage was caused either during its recording, or during

production of the

recaps for the beginning of the second episode.

Episode four famously opens with a BBC caption and a

voiceover warning that the BBC considered that the show was "unsuitable for children

or those of you who may have a nervous disposition". The quality of the caption slide

recording is very poor, but Andrew Martin at the BBC's Windmill Road archive was able to

locate a proper 35mm film of the same caption which has been used to replace the recorded

version.

Good use was made of location film inserts, but the

telecine technology of the time was not very sophisticated and often the film sequences

are poor quality and generally very badly black-crushed, especially in

episode five. In fact,

clips from the same episode five sequences that appear in the recap on the following episode

are much higher quality, but aren't long enough to be inserted back into the episode.

Unfortunately, most of the original inserts no longer exist, so very little can be done to

make these sequences more acceptable. The exception to this are the model shots of the

'Quatermass II' rocket from the last episode, which still exist as 35mm negative and which

were used in this restoration. The image was softened down a little in order that the much

higher resolution didn't make the sequences stick out too much, but the much increased

levels of stability and low-light detail made it well worth doing.

All of the episode recap sections were originally

formed by editing together a compilation culled from the film recordings of the previous

episodes, which were then played out live from telecine. As these sections survive as a

film recording of a telecine playout of another film recording, their quality is much

lower than that of the same scenes in the episodes themselves. So each of the five recaps

were rebuilt during restoration, using the remastered previous episodes as the source.

Mark Ayres certainly

didn't find the audio cleanup on this story quite as straightforward as he had

hoped it might be...

I left this one until last, thinking

that it might take the least amount of work. How wrong I was...

The first job here was to locate a

clean recording of the opening theme music. And, without much ado, a copy of the

original mono Curwen NIXA recording of Holst's The Planets - featuring the

Philharmonic Promenade Orchestra conducted by Sir Adrian Boult - was found in

the BBC Music Library. And when I say "original", I mean "original": an early

33rpm vinyl LP, it was in pretty poor condition, played to death with ingrained

surface noise and awash with crackle. It is, indeed, very probably the self same

disk as used on the original transmission, though for that it was copied first

to 78rpm disk and thence to 35mm mag to be married to the titles film each week.

After a morning spent decrackling and denoising I ended up with a recording

which, while still not perfect, was at least useable, and I replaced it at the

head of each episode in preference to the scratchy optical track, also replacing

longer music-only passages in the recaps.

I then tried to replace the closing

titles music. Both cues used here are pieces by Trevor Duncan from the Boosey &

Hawkes library. For episodes one through five, the track is "Inhumanity", while for episode

six

it's "Project" from "Transitional Scenes Pt 2". Again, we found that the BBC

Library has not retained these 78rpm recordings, and they were not to be found

at Pebble Mill. But while B&H themselves no longer have masters, they were kind

enough to loan me their remaining copies of the original disks. Sadly, however,

it was not possible to get a useable transfer of these done in the time, and a

broadcast turntable with 78rpm playback and a selection of styli is now on my

shopping list! Nevertheless, the closing titles on episode

one were pretty good

(after cleanup) and were themselves used to repair ragged endings on later

episodes.

Cleanup then continued as usual - large

amounts of noise reduction with careful riding of levels, and manual removal of

more stubborn clicks, pops and bumps: nearly 2000 in episode

one for starters.

This manual cleanup takes a long day per episode, and it is necessary to take

frequent breaks - staring at waveforms on a computer monitor can make your eyes

go funny after a while, to say nothing of the RSI from constant clicking and

dragging with the mouse!

There were a few bursts of interference

distortion in episode one - this is

printed-in from the damaged negative

and they are accompanied by corresponding scratches and blemishes on picture. This noise has

been cut around where possible, filtered and re-drawn where not. But some

vestiges remain (sounding, I realised as I checked these masters at the end,

like someone softly passing wind...); with more time it might have been possible

to reduce this some more, but the law of diminishing returns applies!

Throughout episode

two a musical "sting"

(one of a number by George Arnos used in this story, from the Paxton library) is

heard a number of times. Each time, the disk from which it was played (probably

a 78rpm soft acetate "working copy" made from the original) gets more worn -

especially on the run-in where it was cued. Heavier doses of click and crackle

reduction had to be used on each occurrence to clean this up. The same sting -

and, sadly, disk - will return in episode four, disintegrating still further.

Once again, I was very wary of

correcting "mistakes" in this live recording. However, in episode

two when the

truck pulls up to take Dillon away, the studio mixer quite neglected to fade up

the film sound until a few seconds into the shot. As this was so obvious, and

rather distracting, I fixed it.

At about 9:40 in episode

two, as we enter

the "Camp Voluntary Committee Duty Office", the sound mixer fades up the wrong

microphone (one on another set, by the sound of it) and the first couple of

lines of dialogue can barely be heard - there is nothing that can be done about

this. The remainder of this scene is affected by a number of large bassy "bumps"

in the audio - possibly handling noise from a poorly-mounted boom microphone.

These effects have been cut around or filtered as possible. Sadly, the same

affliction was found in a couple of later scenes but, with time running out and

the delivery date looming (I was working on this section between Christmas and

New Year), I was unable to be as thorough here as I would have liked. Hence a

fairly steep low cut filter was applied generally to soften the effect without

cutting into dialogue.

The levels on episode

three were a tad high

in places, especially in the opening scene in the Inquiry where the sound mixer

had used a clever perspective mixing technique to heighten the tension, so I

gently rode the gain to correct this - while maintaining the overall dynamic.

This episode was generally pretty clean (indeed some passages were so clean they

could have com off mag - thankfully, after the terrible state of the first two

programmes!). The worst section was that around the picnic sequence - the

dialogue is very noisy and rather "scratchy"; there was little more that could

be done here than some fairly heavy denoise and a lot of click removal.

And it's at about this point in the

proceedings that a massive earthquake in the Indian Ocean sends huge Tsunamis to

devastate hundreds of miles of the surrounding coastline across numerous

countries. I sit back from the computer for minutes at a time over the next few

days as everything finds - as it often does in this mad world of ours - a new

perspective. Drawing clicks out of the soundtracks of 50-year-old TV shows

suddenly seems - as indeed it is - desperately trivial. Nevertheless, it is how

I earn my living, it is how I feed, clothe, and educate my sons. But a

proportion of what I am earning on this job will now go towards the disaster

relief fund.

The restoration proceeds pretty much as

before, though some scenes come as a shock: the sequence in episode

four where the

meteorite hits the Comedy Irish Pub was in a terrible state - especially where

the zombies enter - and many hundreds of clicks and bumps were removed in the

space of a couple of minutes (and a few hours hunched over the Mac!). Episode

five

proved to be the hissiest of the six, while the final episode turned out to be

generally pretty clean under all the surface noise. In this episode I did help

the dynamics at a few points (the rocket launch, the impact with the asteroid,

and the nuclear detonation at the end), and I repaired a hole in the soundtrack

where the studio master fader appears to have been ducked accidentally. A word

or two was missing here, so I have nicked one from elsewhere to cover - but I'm

not telling where this was! Nothing could - or should - be done about the

atmosphere on the alien asteroid, which sounds like a plumbing disaster in a

rather palatial bathroom! Similarly the asteroid's very wooden-sounding surface.

One problem was impossible to fix, and that comes near the end: Leo is holding Quatermass at gunpoint, "You have done as intended!". There is what sounds like

a film break here, and it exists on both transfers I have heard, the word

"intended" being interrupted with a large blip. All I was able to do here is to

soften the "blip" so that is does not sound so bad.

Picture restoration was

more a case of damage limitation due to the poor resolution of the

source, especially film inserts. Two passes of deblobbing were done to remove

the worst of the dirt, sparkle and scratches. Electrical interference

affects many short sections particularly in episodes

one and two These have been

improved where possible but without a large budget and lots of time, complete

repair would be impossible. In several places throughout the episodes one or two

frames are missing from the print resulting in a picture jump. These have been

repaired by generating new in-between frames and trimming the end of the shot to

maintain audio sync and episode length.

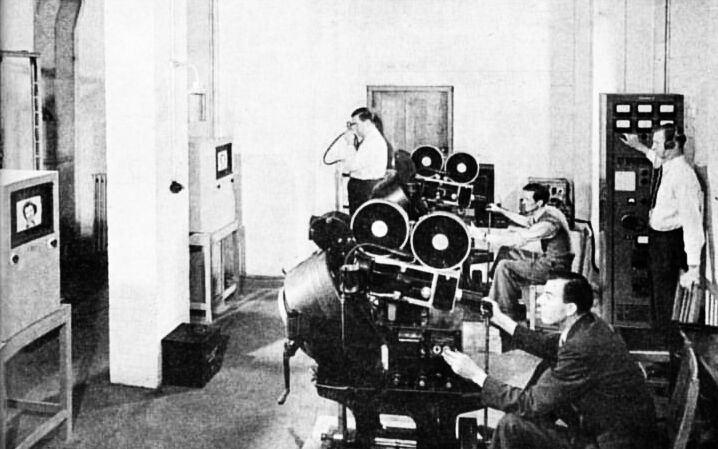

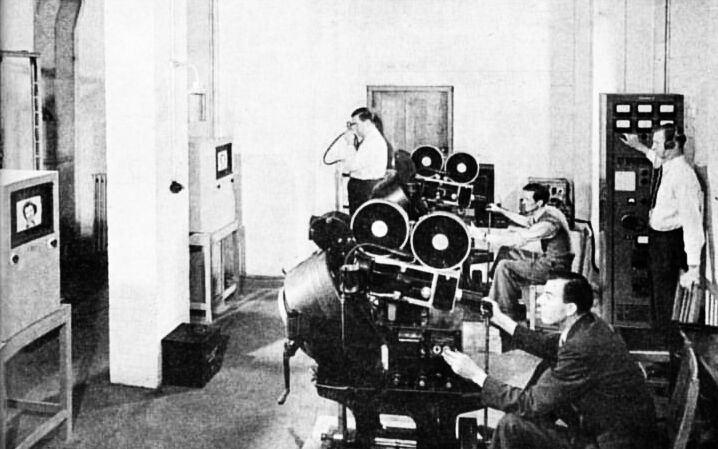

The Quatermass Experiment was recorded on Alexandra

Palace's Mechau film recorders - actually a clever re-engineering of a Mechau projector

mechanism. Unlike a conventional projector, where the film motion is intermittent due to

the frame being pulled down into position and stopped before the shutter opens, the Mechau

system used a continuous film motion, with the position of the moving image

accurately tracked back to the lens by rotating mirrors. Film recording at Alexandra

Palace consisted of a pair of Mechau units, each focused onto a high-quality monitor

screen positioned a few feet in front of them. The area was lit only by a dull red light

during operation, as the optical path was open to the room instead of being totally

enclosed as it would be in later film recorders. There was no servo system as such to link

the recorded framerate to that of the video signal - instead, the operators would vary the

speed of the recorder's motor using a long joystick device, with reference to a crude

meter which allowed them to match the frame rate to video. The Mechau's could be used as

telecines by reversing the process and placing a television camera where the

film recording monitor would have been! Although the Mechau recorded both fields, the image

resolution was limited by the optical system used to scan the film, so the overall image

quality is worse than Quatermass II, although the lack of visible line

structure helps somewhat. The optical soundtrack was recorded using the crude

variable-density method, which would be superseded by variable-area recording. The same

recorders were used the following year to record Cartier's production of George Orwell's Nineteen

Eighty-Four, which is noticeably better quality. As with Quatermass II,

it seems to be the quality of the Emitron studio cameras that really causes problems, with

the same visible problems with large areas of black and white shading and very vignetted

images.

The Quatermass Experiment was recorded on Alexandra

Palace's Mechau film recorders - actually a clever re-engineering of a Mechau projector

mechanism. Unlike a conventional projector, where the film motion is intermittent due to

the frame being pulled down into position and stopped before the shutter opens, the Mechau

system used a continuous film motion, with the position of the moving image

accurately tracked back to the lens by rotating mirrors. Film recording at Alexandra

Palace consisted of a pair of Mechau units, each focused onto a high-quality monitor

screen positioned a few feet in front of them. The area was lit only by a dull red light

during operation, as the optical path was open to the room instead of being totally

enclosed as it would be in later film recorders. There was no servo system as such to link

the recorded framerate to that of the video signal - instead, the operators would vary the

speed of the recorder's motor using a long joystick device, with reference to a crude

meter which allowed them to match the frame rate to video. The Mechau's could be used as

telecines by reversing the process and placing a television camera where the

film recording monitor would have been! Although the Mechau recorded both fields, the image

resolution was limited by the optical system used to scan the film, so the overall image

quality is worse than Quatermass II, although the lack of visible line

structure helps somewhat. The optical soundtrack was recorded using the crude

variable-density method, which would be superseded by variable-area recording. The same

recorders were used the following year to record Cartier's production of George Orwell's Nineteen

Eighty-Four, which is noticeably better quality. As with Quatermass II,

it seems to be the quality of the Emitron studio cameras that really causes problems, with

the same visible problems with large areas of black and white shading and very vignetted

images.

Episode two's recording is of a lower quality than

episode

one and there are some nasty technical problems on display. At one point the image

collapses vertically, before bouncing back, turning negative, then positive again - but

only in the top half of the screen - before finally settling down. For most of the second

half, an insect can be see sitting on the film recorder monitor, its image indelibly burnt

into the film recording. At several points in the recording the picture is affected by

severe amounts of random impulse noise, probably caused by a bad connection or a noisy thermionic valve in the video amplifier. High levels of noise reduction were applied

during remastering in order to try to bring this under control. Part of Judith Caroon's

dialogue is lost immediately following a reel join roughly 13 minutes into the episode on

the print. However the negative of the reel immediately preceding the join has the

dialogue intact, so we were able to recover it.

Luckily Mark Ayres had

less of a problem with the sound this time around...

Despite the poor quality of the

pictures for this story the audio recordings - underneath all the noise - are

actually pretty good. For a start, the levels are far more consistent than on

the Pit, and I only needed to tweak them by a decibel or two here and there.

I was unable to locate a copy of the

original recording of the opening music used on this story - "Mars" from Gustav

Holst's "The Planets". The recording is conducted by Albert Coates (who also

conducted the public premiere of the work in 1920) and appeared on the HMV

label. Research suggests that the recording was actually made in 1929, and would

certainly have been played in live to the transmission of the episodes from 78

rpm disk. Strangely, the music at the start of episode one is played at the wrong

speed - so fast that it is 3 semitones high. This may have been deliberate (to

give a greater sense of urgency to the start of the story) or in error:

So-called "78s" were often recorded at different speeds, anything from 60rpm to

over 100rpm, and the playback deck may have been set at the wrong speed. The

opening titles at the beginning of episode one have a clean start, but there is a

film break leading to a discontinuity in the music. The music is truncated at

the start of the second episode, and this time riddled with dropout. Hence I

repaired the film break in episode one with some nifty editing, then copied the

file and varispeeded it down by 3 semitones to use at the start of

episode two.

The episodes were subjected to some

pretty severe noise reduction and passed through a de-crackle plugin at a high

setting to remove most of the film surface noise. Noise reduction thresholds had

to be "ridden" at times to make sure that some very quiet dialogue was not

removed. But the noise reduction could not deal with the worst of the clicks and

pops - I manually drew out over 500 large clicks in episode

one, and 1200 in episode two (for trivia fans that's around 1 every 3.7 seconds in

episode one, 1 every 1.6

seconds in episode two!), while even more severe clicks and bumps were cut out and

the spaces filled with patch noise lifted from elsewhere in the episodes.

The original music used on this story

proved impossible to locate in time but I did use a good take of music at one

point in episode one to replace a poorer take later: Trevor Duncan's "Lost in

Space" which was used over a couple of the long black "passing time" passages,

was good on the first but very unstable on the second, so the first was copied

up to cover.

One major snag occurred in episode two.

On the existing print, there is a line missing, "I wanted him to come back more

than anything else in the w(orld)" at the reel change - the picture is there,

but there is a big hole in the soundtrack. As it had been decided to use the

existing print as the source, Steve Roberts had a new

transfer of just these few seconds of the negative made so that the soundtrack

could be repaired - but there was a problem with this. The soundtrack is a

variable area optical track - in other words the waveform is represented on the

prints by an optically printed pattern where waveform peaks are shown by a wider

transparent area, and troughs (silence) by black. This is a terrific system in

that the black passes no light and therefore also lessens the inherent noise in

quiet passages. Obviously, the clear area picks up dirt and scratches so louder

passages tend to be noisier - leading to the characteristic optical whoosh of

sibilance on some tracks where the signal is not enough to cover that greater

level of noise. However, on the negative of course, the silence is represented

by a wide clear area, and the peaks by darkness - hence, a very high "ground

noise" level which all but masked the line we wanted. I have, therefore, had to

use a severe amount of noise reduction on this one line to try to match it in,

so severe that the "glassiness" of the noise reduction is apparent - yet I felt

it preferable, and less distracting, than a sudden burst of noise at this point.

In an ideal world, of course, we would have had a new print struck, but it could

not really be justified for a single line.

For many years, there have been a number of theories

put forward to try to explain why only the first two episodes of the show still exist. The

favourite rumour for many years was that there had been a technician's strike and that

industrial action had prevented the recording - although researchers have been unable to

find any record of such action. Later it was claimed that the S.Tel.E. (BBC parlance for

the Senior Television Engineer) responsible for the recording area had been so

disappointed by the results from the first two recordings that he refused to allow them to

continue. To further complicate the matter, Canadian TV listings appear to indicate that

the first two episodes had been scheduled for transmission in Canada, although it is

unlikely that the transmissions actually took place. Records on INFAX, the BBC Archives

database, indicate that the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation hold copies of the first two

episodes as 16mm reduction prints, adding further weight to this story.

The interesting question is... why

was the serial was even

being recorded in the first place? Whilst it may have been very useful to record it for

recap purposes, the evidence from the extant second episode shows that the recap took the

form of a replay of one of the proper 35mm film sequences from

episode one, coupled with a

camera pan down the actors standing in a line as a narrator covered the events of the

previous episode. Is this always how it was intended to be? Or was the quality of the

first episode's recording so poor that the film-recorded studio material was deemed to be

unsuitable for use even in the recaps, necessitating the use of this particular technique?

Was it being recorded for Canadian TV and did somebody call a halt after the second

episode when it became clear that the technical quality had dropped sharply - and that

there was a fly sitting bang in the middle of the screen for much of the episode? We will

probably never know the complete answer... but all the evidence sadly seems to suggest

that recording was stopped after episode two.

Footnote

All of the restoration

work was carried out by a small and experienced team, without whose dedication

and skills a release of this quality simply would not be possible. Telecine

transfers, grading, editing and noise reduction was carried by Jonathan Wood at

BBC Resources. Picture cleanup and VidFIRE processing was carried out by a

specialist team at SVS. Audio restoration was by Mark Ayres. The

project supervisor was Steve Roberts. The team would like to thank BBC

Information and Archives - and in particular Andrew Martin at the Windmill

Road archive - for arranging complete access to the Quatermass master materials

during the project.

Copyright Steve Roberts

/ Mark Ayres, January 2005. No duplication without written consent!

The three Quatermass serials - The

Quatermass Experiment (1953), Quatermass II (1955) and Quatermass

and the Pit (1958) - were produced by the legendary Rudolph Cartier, in

an era in which live television transmission was the norm and any kind of

television recording system was still in its infancy. In fact, the last serial

was transmitted only scant months after the first Ampex Quadruplex video tape

recorder was delivered to the BBC (in July 1958) and the second machine was not

delivered until early 1959. It would be a few more years before the BBC were

routinely using videotape for drama programmes. All three serials were transmitted live from BBC studios in

London, using the 405-line television system - literally a live, multi-camera studio

performance with pre-filmed 35mm inserts played in from telecine. These inserts served the

dual role of allowing the story to spread to locations beyond the confines of the

television studio, and of allowing time for the actors and cameras to move to the next

studio set.

The three Quatermass serials - The

Quatermass Experiment (1953), Quatermass II (1955) and Quatermass

and the Pit (1958) - were produced by the legendary Rudolph Cartier, in

an era in which live television transmission was the norm and any kind of

television recording system was still in its infancy. In fact, the last serial

was transmitted only scant months after the first Ampex Quadruplex video tape

recorder was delivered to the BBC (in July 1958) and the second machine was not

delivered until early 1959. It would be a few more years before the BBC were

routinely using videotape for drama programmes. All three serials were transmitted live from BBC studios in

London, using the 405-line television system - literally a live, multi-camera studio

performance with pre-filmed 35mm inserts played in from telecine. These inserts served the

dual role of allowing the story to spread to locations beyond the confines of the

television studio, and of allowing time for the actors and cameras to move to the next

studio set. Quatermass and the Pit was performed from

Riverside Studios in Hammersmith and recorded using a 35mm stored-field film recording

system. This was a system designed to get round the mechanical impossibility of advancing

the film forward a frame within the 'field blanking interval' - the very short dead time

between the two interlaced TV fields that make up one frame. Only a few years earlier, Quatermass

II had been recorded using a suppressed-field recorder, which only exposed one of

the two video fields to film, using the duration of the second field to close the shutter

and move the film on in readiness to expose the next frame. This meant that the vertical

resolution of the suppressed-field image was less than two hundred lines, resulting in a

very coarse, steppy image. Stored-field got around this problem by 'storing' one field

using the long decay time of the phosphor coating on the film recorder's cathode ray tube

and allowing an entire 20mS field period to allow the film to be advanced to the next

frame. During the first field, the camera shutter would be closed and the film would be be

advanced.

Quatermass and the Pit was performed from

Riverside Studios in Hammersmith and recorded using a 35mm stored-field film recording

system. This was a system designed to get round the mechanical impossibility of advancing

the film forward a frame within the 'field blanking interval' - the very short dead time

between the two interlaced TV fields that make up one frame. Only a few years earlier, Quatermass

II had been recorded using a suppressed-field recorder, which only exposed one of

the two video fields to film, using the duration of the second field to close the shutter

and move the film on in readiness to expose the next frame. This meant that the vertical

resolution of the suppressed-field image was less than two hundred lines, resulting in a

very coarse, steppy image. Stored-field got around this problem by 'storing' one field

using the long decay time of the phosphor coating on the film recorder's cathode ray tube

and allowing an entire 20mS field period to allow the film to be advanced to the next

frame. During the first field, the camera shutter would be closed and the film would be be

advanced.

The majority of Quatermass II was recorded from Lime

Grove studios in Shepherd's Bush using a 35mm suppressed-field film recorder and as such

it has much poorer image quality than Quatermass and the Pit. The

television line structure on these episodes is very visible and the picture itself is made

up of less than two hundred lines. For some reason episode three was recorded on a

different kind of recorder to the other episodes - it was probably a pair of Moye-Mechau

recorders (an upgraded version of the machine used two years earlier to record The

Quatermass Experiment, which used a Mechau mirror mechanism and a Moye camera).

The optical soundtracks produced by both these recorders was of the higher-quality

variable-area type - a significant improvment on the variable-density recording used on

Alexandra Palace's Mechau machines.

The majority of Quatermass II was recorded from Lime

Grove studios in Shepherd's Bush using a 35mm suppressed-field film recorder and as such

it has much poorer image quality than Quatermass and the Pit. The

television line structure on these episodes is very visible and the picture itself is made

up of less than two hundred lines. For some reason episode three was recorded on a

different kind of recorder to the other episodes - it was probably a pair of Moye-Mechau

recorders (an upgraded version of the machine used two years earlier to record The

Quatermass Experiment, which used a Mechau mirror mechanism and a Moye camera).

The optical soundtracks produced by both these recorders was of the higher-quality

variable-area type - a significant improvment on the variable-density recording used on

Alexandra Palace's Mechau machines. The Quatermass Experiment was recorded on Alexandra

Palace's Mechau film recorders - actually a clever re-engineering of a Mechau projector

mechanism. Unlike a conventional projector, where the film motion is intermittent due to

the frame being pulled down into position and stopped before the shutter opens, the Mechau

system used a continuous film motion, with the position of the moving image

accurately tracked back to the lens by rotating mirrors. Film recording at Alexandra

Palace consisted of a pair of Mechau units, each focused onto a high-quality monitor

screen positioned a few feet in front of them. The area was lit only by a dull red light

during operation, as the optical path was open to the room instead of being totally

enclosed as it would be in later film recorders. There was no servo system as such to link

the recorded framerate to that of the video signal - instead, the operators would vary the

speed of the recorder's motor using a long joystick device, with reference to a crude

meter which allowed them to match the frame rate to video. The Mechau's could be used as

telecines by reversing the process and placing a television camera where the

film recording monitor would have been! Although the Mechau recorded both fields, the image

resolution was limited by the optical system used to scan the film, so the overall image

quality is worse than Quatermass II, although the lack of visible line

structure helps somewhat. The optical soundtrack was recorded using the crude

variable-density method, which would be superseded by variable-area recording. The same

recorders were used the following year to record Cartier's production of George Orwell's Nineteen

Eighty-Four, which is noticeably better quality. As with Quatermass II,

it seems to be the quality of the Emitron studio cameras that really causes problems, with

the same visible problems with large areas of black and white shading and very vignetted

images.

The Quatermass Experiment was recorded on Alexandra

Palace's Mechau film recorders - actually a clever re-engineering of a Mechau projector

mechanism. Unlike a conventional projector, where the film motion is intermittent due to

the frame being pulled down into position and stopped before the shutter opens, the Mechau

system used a continuous film motion, with the position of the moving image

accurately tracked back to the lens by rotating mirrors. Film recording at Alexandra

Palace consisted of a pair of Mechau units, each focused onto a high-quality monitor

screen positioned a few feet in front of them. The area was lit only by a dull red light

during operation, as the optical path was open to the room instead of being totally

enclosed as it would be in later film recorders. There was no servo system as such to link

the recorded framerate to that of the video signal - instead, the operators would vary the

speed of the recorder's motor using a long joystick device, with reference to a crude

meter which allowed them to match the frame rate to video. The Mechau's could be used as

telecines by reversing the process and placing a television camera where the

film recording monitor would have been! Although the Mechau recorded both fields, the image

resolution was limited by the optical system used to scan the film, so the overall image

quality is worse than Quatermass II, although the lack of visible line

structure helps somewhat. The optical soundtrack was recorded using the crude

variable-density method, which would be superseded by variable-area recording. The same

recorders were used the following year to record Cartier's production of George Orwell's Nineteen

Eighty-Four, which is noticeably better quality. As with Quatermass II,

it seems to be the quality of the Emitron studio cameras that really causes problems, with

the same visible problems with large areas of black and white shading and very vignetted

images.